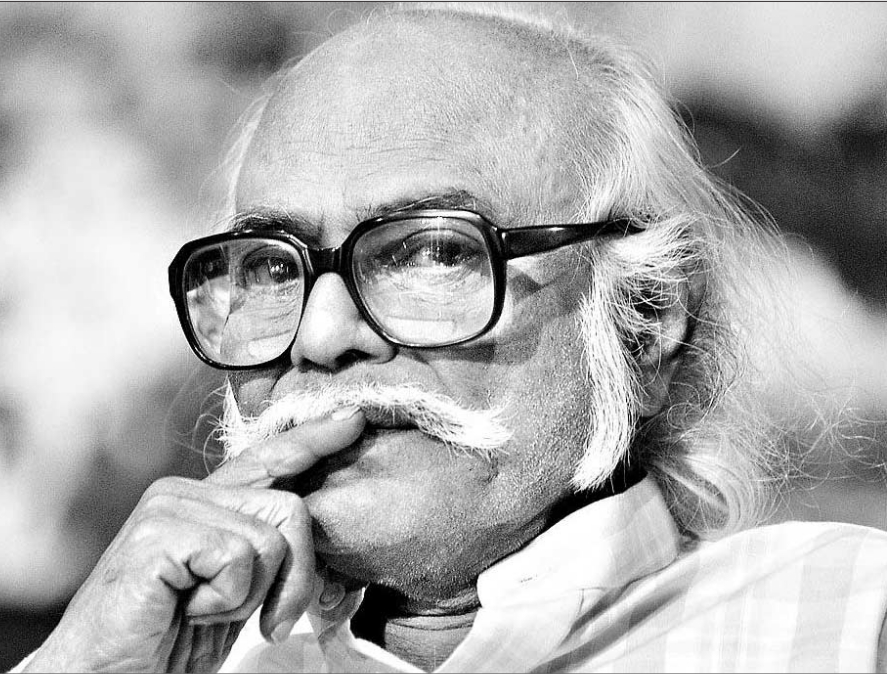

Subash Jeyan profiles D. Jayakanthan recently awarded the Jnanpith Award for 2002.

(Published in The Hindu Literary Review on April 3, 2005.)

BORN in 1934, Jayakanthan has been and still is witness to some momentous events in Indian and world history: the Second World War, Independence, the assassination of Gandhiji, the growth of the Dravidian movements in the South, post-Independence politics, the rise of the BJP in national politics and globalisation. Through it all, he has not just been a witness but an active participant, trying to shape changes in society through his writings (more than 200 short stories, 40 novels and 15 collections of essays) and action. He contested the 1977 parliamentary elections as an independent from T. Nagar Constituency in Chennai. As he observes in one of his essays (“Therthalil Ninra Kathai”), he tried to establish a model code of conduct for candidates. He got 481 votes. May not be much, but he believes that he succeeded in his endeavour because he got almost 500 voters to the polling booth who wouldn’t have otherwise voted.

The logic of stories

And through it all, the man himself, and his writings too, have changed. It would have been odd if they hadn’t. “There has been a lot of changes in society and human life. According to that writing should also change,” he says. But, as many articles since he received the Jnanpith Award for 2002 have pointed out, nobody expected a story like Hara Hara Sankara to come out of his pen. Published in January 2005, the short novel has as its central incident the arrest of the Kanchi Sankaracharya. But Jayakanthan is not one bit defensive. It is not his fault that such a novel isn’t expected of him, he says. “Expect it from me now, know me now,” he says. “A lot of things happen in life and there are newspapers to report them. I am not doing that. Based on something that happened, with all good intentions, I use my imagination to write a story. But I am not defending anybody or accusing anyone. I am telling a story.” And stories have their own logic. One is reminded of the “controversy” over the ending of his Sahitya Akademi award-winning novel Sila Nerangalil Sila Manithargal. Defending the ending, Jayakanthan argues in the foreword to that novel that literary experience has its own logic and that the writer at any rate is not a street performer to please everyone.

Humanist first

His writings may not please everyone, but those who have read his stories will realise that Jayakanthan is first and foremost a humanist and his vision has always been inclusive. Whether it is Unnaippol Oruvan (first published as a novel in 1964) or Sila Nerangalil Sila Manithargal (1970), or its “sequel” Gangai Engae Pogiral? (1978) or the short story “Yuga Santhi” (2000), his characters come from every spectrum of society. He can portray a Chitti, whose life everyday in the slums is a struggle, with as much authenticity and honesty as he can portray a Ganga, caught in a typical middle-class environment though her situation is anything but typical. Even in a strongly Leftist-influenced story like Moongil Kaattu Nila (published in 1979 in the magazine he edited, Kalpana), where the exploitative class structures of society get highlighted, the narrator, from the land-owning “zamindar” family gets his due honest treatment as a character.

Whatever class his characters come from, one strong motif in his stories is the belief that people need to find their respective purposes in life. Most of his remarkable characters, whether it is Chitti, Ganga, Prabhu or Gowri Patti in “Yuga Santhi”, all manage to emerge successful, against tremendous odds, in their journeys to discover and moor themselves to a governing principle and purpose in their lives. Says Jayakanthan: “Nothing has a right to live without purpose. We don’t create our lives but we create in our lives. Sometimes people may not be able to articulate the purpose in their lives. That’s what a writer does. He gives… voice to those who can’t speak; eyes to those who can’t see; a mind to those who can’t think; a heart to those who can’t feel.”

He believes in the interventionist function of literature, in the ability of literature “to refuse and change certain social norms and to bring for review before time certain unjust verdicts”, in the capacity of literature to show things as they ought to be. Dissent according to him is an essential function of literature. But its ultimate aim should be harmony, he feels strongly. Perhaps it is this vision of ultimate harmony, of trying to work towards it that has made him soften his stand on many things including the Dravidian movements and the BJP (movements which he opposed politically and still does). There are echoes of his early Gandhian influence when he says that we shouldn’t destroy our enemies but change them. “I am a democrat basically. I accept changes, I also change; that is a sign of growth and maturity,” he says.

Though he hasn’t stopped writing short stories, it has been quite a while since he wrote a full-length novel. Any particular reasons? “I have as much freedom not to write as I have the freedom to write,” he responds. “Previously I felt the need to write often; only occasionally lately.” And one thing that hasn’t changed much, you realise, is his celebrated capacity for anger. “Don’t mistake vehemence for anger,” he smiles.