Ashokamitran’s prose is underplayed and his sardonic wit can be refreshing. Subash Jeyan

(Published in The Hindu Literary Review on March 6, 2005.)

IT seems a difficult task to classify Mole!at first. Ashokamitran had spent parts of 1973-74 at the University of Iowa in the United States attending an International Writing Programme. Mole!too is set in the University during the same period and has an international collection of authors and poets attending a writing programme as its subject. The narrator, a writer from Chennai, though he is never explicitly identified or even directly named, could be Ashokamitran himself. Certain characters in the novel variously mangle the narrator’s name as “Tagarazan” and “Takka Rayan” and Ashokamitran’s real name, we are told, is Thyagarajan.

Episodic structure

So, is it a travelogue or a memoir or a novel? The fact that its structure seems episodic rather than linear or progressive only adds to the “complication”. As A.R. Venkatachalapathy points out in his Afterword to the novel, “his short stories are but parts of a novel and his novels a collection of short stories in a certain order” (p.154). When originally published in Tamil in 1985, certain chapters were left out to keep the number of pages below 200, which were independently published in magazines as short stories. These now find their way back in the English translation.

If chapters can be left out or added at will, we’ll have to look for the sustaining structure elsewhere. At the narrative level, it seems a collection of disparate events lumped together between a very basic narrative device of an opening chapter where the narrator flies out of Colombo and the last chapter where he is headed to the airport, flying home. Between these two departures, the narrator’s personal arrival at an equilibrium is what gives the novel its thematic tone and unity.

This personal arrival traverses a landscape of differences and dislocation to reach a perception of a universal essence, if you will, of humanity. It is significant that the opening chapter, where the narrator flies out to the U.S., is set in Colombo. It could as well have been Chennai. But Colombo immediately thematises the narrator’s sense of being a stranger in a strange land which only heightens on his arrival in the U.S. He bumbles his way around, totally lost amongst elevators, free newspapers and stoves that don’t need “matches”, in a world oriented along very different lines from the one he is familiar with. And he is awestruck by some of the other writers, as much strangers to the environment as he himself is, who are able to quickly make themselves at home soon after arrival.

The characters he is forced to live with challenge his sense of the normal in their own different ways. Ilaria, a student, drives a bus part-time to finance her studies; Choe, his South Korean room mate with very different culinary tastes; Abie Gubegna’s taste for expensive western clothes and the squalor of his room; Bravo, the Peruvian novelist who makes the novel “resemble the circuitry of an electronic appliance” and who turns “literature into a technology of precision”. But the narrator chaffs out the “superficial” things about people and connects with them at a “deeper” level of fundamental human emotions: Ilaria as a fool for love, Choe in his personal loss, Abie with his jealousies and Bravo with his petty betrayals. In their foibles and weaknesses, they retain their humanity and the narrator, his normalcy.

In fact, the narrator becomes the mole because of this uncanny ability to sense out the essence of people. From a bumbling outsider he becomes a person people come to depend on, to whom they can reveal their innermost selves. It is only appropriate that the narrative highpoint of the novel, climax if you will, if it were a linear narrative, comes in a chapter titled “Hall of Mirrors” where Jim Parker, a black artist, is able to see through to the essence of the narrator himself.

Aesthetic of the ordinary

Ashokamitran’s prose is underplayed, much of which has been ably captured in N. Kalyan Raman’s translation, and his sardonic wit can be refreshing. His has been called an “aesthetic of the ordinary” but his prose can sometimes become just ordinary. And predictable, because each of the chapters maps out the narrator’s encounter with difference and his ultimate neutralisation of that difference along the same lines. And the conception of experience as something that doesn’t lead one out of oneself can be problematic. Your mileage, of course, may vary.

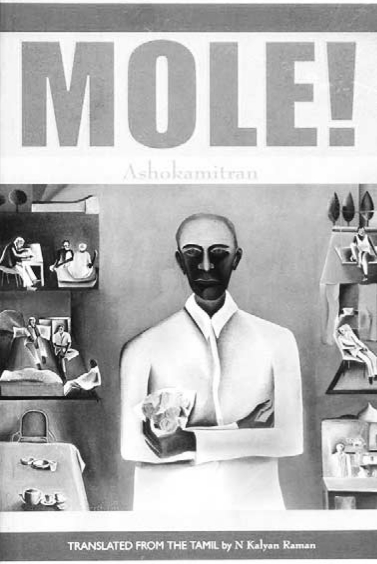

Mole!, Ashokamitran, translated from the Tamil by N. Kalyan Raman, Orient Longman, 2005, p.161, Rs. 185.