It is always a pleasure to go straight to Ramanujan’s own writing and catch him at the moment of chasing an image in all its ironic clarity, says SUBASH JEYAN.

(Published in The Hindu Sunday Magazine on December 14, 2003.)

Anyone translating a poem into a foreign language, is, at the same time, trying to translate a foreign reader into a native one. -A.K. Ramanujan

TRANSLATION for Ramanujan was an extension of writing — one translates what one would have liked to have written, out of envy, out of a need to appropriate, he often said in many of his introductions, afterwords and interviews. And one suspects, translation, and by extension writing, for Ramanujan was also a process of translating oneself from a foreign writer into a native one. One of the predicaments of Indian modernity by which reclaiming a tradition, or traditions, through study and scholarship is one of the options of reforging the strands that make up one’s identity.

Given the many locations mapped by modernity (“… by a curious perversity I read Tamil constantly in the Kannada area, Kannada in the Tamil area, studied and taught English in India, and India and Indian languages in the U.S.;” Interview with Chirantan Kulshrestha), Ramanujan, so to say, had an embarrassment of riches to tap into. But reclaiming a tradition is a very different thing from inheriting a lived tradition that still survives, in whatever mutated form shaped by the pressures and contingencies of being lived in, in the fringes of a modernist’s gaze. The bhakti poetry of the Alvars, for instance, when one read them, as part of the Tamil syllabus in high school or when one heard them seeping out of early-morning childhood temples, had none of the reformatory urgency that Ramanujan sees in them. Perhaps because tradition had assimilated the original impulses, perhaps because one didn’t have to relocate oneself in history to avail oneself of the background noises to living, or perhaps simply because, the easy way out of it all, one didn’t have good enough teachers.

Because one has to, out of necessity, approach tradition with the very tools which dispossessed one of tradition in the first place, conscious reclamation of a tradition then is also to a certain extent an unconscious, but legitimate, remaking of it to suit one’s present contingencies. And Ramanujan’s contingencies enact in many ways the contradictions of a modern Indian writer, particularly one writing in English.

The interview with Chirantan Kulshrestha quoted above, given in the pre-Rushdie year of 1970 and included in this collection, is a telling entry point into these contradictions. While Ramanujan holds very strongly that the language one writes in is not a matter of choice, he is also aware of the pitfalls of writing in a “second language” like English: “When one writes in a second language not learned in childhood, superimposed on a first, one may effectively cut oneself off from one’s childhood. A great deal of what we are in life and in writing goes back to that period when language was being formed inside, forming us, forming the world of concepts, the style of our perceptions. No man can deny or insulate that source of his sensibility without peril.”

And later, “Most of us who for some reason or other write in English have probably written ourselves into the margin, because of such splits in our persons and in our language. And they are big splits. With a foreign language like English, we also get separated from the great community of people in India. We become dependent on cliques and coffee-house ‘elites’.”

So one discovers and relocates oneself into the formalism of Sangam poetry, the subversive strains of bhakti poetry, into traditions where bilingualism was a norm with counter-cultures straining against monolithic pan-Indian streams. One creates one’s own fraternity of poets, a tradition to which one belongs if only through parallels of departure.

But, the above quote is telling because the Tamil Nadu of the 1940s and 1950s, in Periyar’s Dravidian movement, in its language politics, and in its social narratives and particularly in its films, was in many ways reenacting these impulses anew vis-à-vis the newly emerging “national” mainstream and the many splits inherent in its formation. And Ramanujan, at least in his formal writings, seems to have been impervious to it. (It is a different matter that some of the latter-day inheritors of the legacy turned the ideology on its head: MGR was a famously prominent patron of temples in Karnataka while in films directors like Mani Ratnam and A.R. Rahman emerged into popularity and acclaim by deliberately eschewing the ‘regional’ and catering to a pan-Indian, cosmopolitan audience.)

Here, then, are Ramanujan’s collected attempts at translocating himself. The book brings in one volume his poetry and translations: the three volumes of poetry that he published in his lifetime, the posthumous Uncollected Poems and The Black Hen from Collected Poems, The Interior Landscape, Poems of Love and War, Speaking of Siva and Hymns for the Drowning. By way of introduction to the writer, we have Molly Daniels-Ramanujan’s curiously impersonal and rather dull exposition of Ramanujan’s poetry and Vinay Dharwadker’s introduction to the Collected Poems written in 1994. While an up-to-date introduction would have been welcome, it is a pleasure, as always, to go straight to Ramanujan’s own writing and catch him at the moment of chasing an image in all its ironic clarity (“Still Life”):

When she left me

after lunch, I read

for a while.

But I suddenly wanted

to look again

and I saw the half-eaten

sandwich,

bread,

lettuce and salami,

all carrying the shape

of her bite.

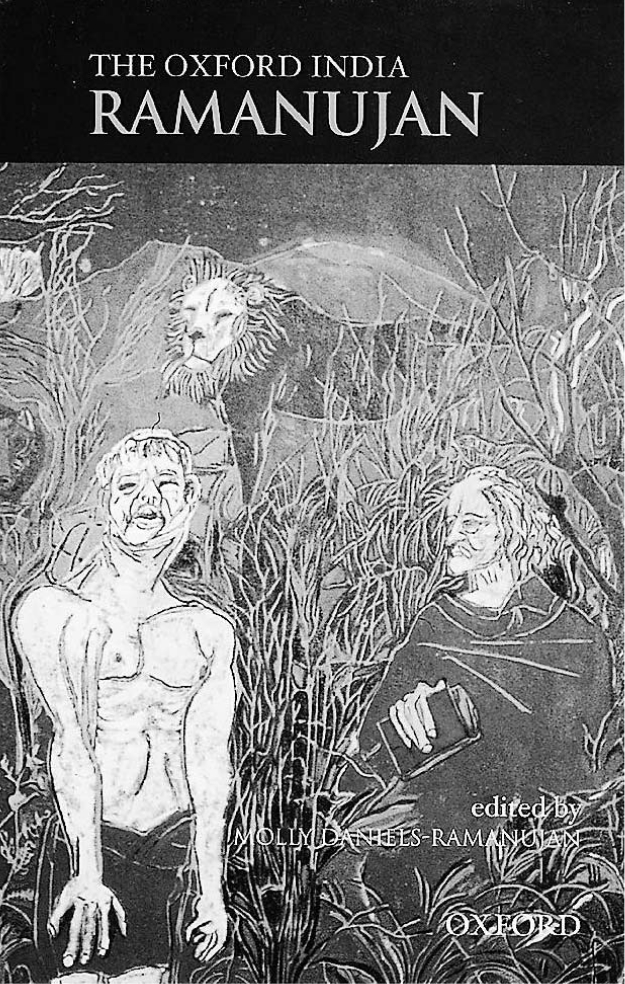

The Oxford India Ramanujan, edited by Molly Daniels-Ramanujan, OUP, 2004, Rs. 875.