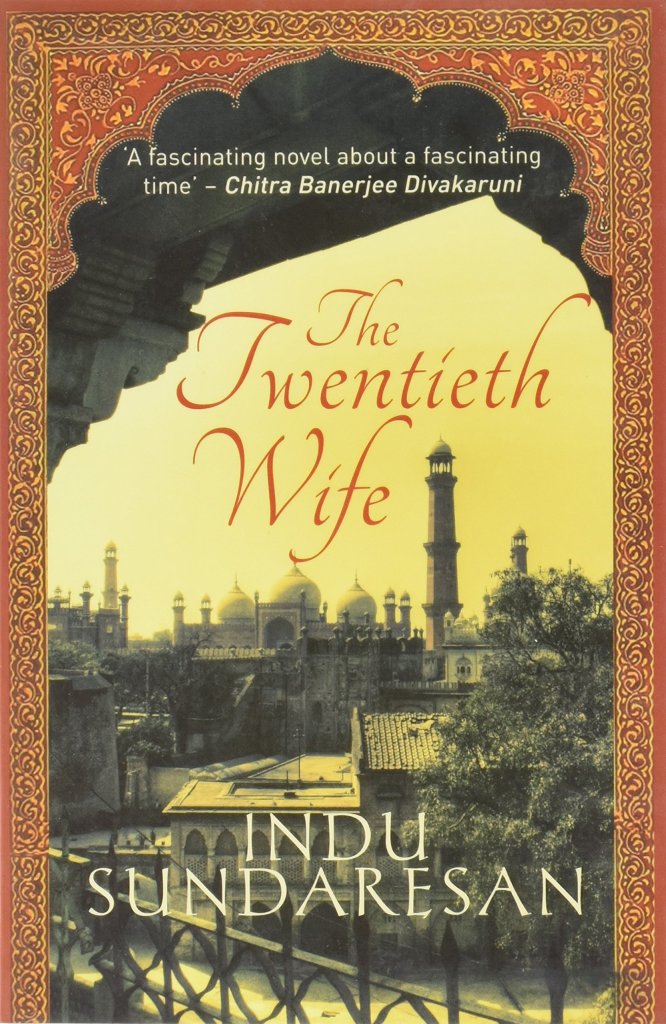

Review of The Twentieth Wife by Indu Sundaresan, published in The Hindu Literary Review of August 4, 2002

THE first British trading ship, the Hector, commanded by William Hawkins, landed in Surat in 1608, during the reign of Jehangir. The Mughal empire was at its peak and drawing from his diaries and those of other “ambassadors” who followed, Philip Mason, in one of those justifications for the empire that goes under the garb of history (The Founders and The Guardians, later abridged into one volume as The Men who Ruled India) writes: “This then was the India in which the first Englishmen found themselves. A brilliant court, profuse in display…; long processions of elephants with trappings of gold and silver, silks, jewels, servants, fans of peacock feathers, glowing carpets, horses from Persia and Arabia; it was not surprising that stories went to Europe of the wealth of India” (p.12).

Splendour on a scale unknown in Europe, “But it is depressing for a Western mind to turn in the same period from Europe to India, not only because of the degree of cruelty and human misery is on the whole greater, but because there is no sign of growth in any desirable or even definite direction. There is none of that steady development of a principle or an institution…. Instead there is a melancholy record of insurrection, treachery and murder. The sons of each Emperor are rivals for the throne; before he is dead they are in arms against each other and against him. The most able and unscrupulous imprisons, blinds or kills the rest, as a queen bee stabs each young queen struggling out of her cell” (p.13). And elsewhere, “India too would one day be free…. But for the present it was guardianship India needed…. That was the mixture, very good for the child, to be given firmly and taken without fuss” (xiv-xv).

Commercial interests subsumed under messianic moral imperatives, Mason fairly encapsulates Europe’s otherisation of the Orient, the domestication of a disturbance and a threat to its sense of the self. The Masons of this world now have their Saids and Rushdies. And now, it seems, they also have their Sundaresans. Indu Sundaresan’s novel The Twentieth Wife looks at exactly the same period in Indian history that Mason is referring to: the reigns of Akbar and Jehangir. William Hawkins, in fact, is a character in the novel.

Writing in the United States, midnight’s children and grandchildren are waking up to new dawns, and what does one do with the history of the country one has left behind, considering all the things that have already been done with it? Indu Sundaresan has impressive interventionist intentions: talking of the Mughal empire and its kings, she says, “There are few mentions of the women these kings married or of the power they exercised. The Twentieth Wife seeks to fill that gap” (p.387). And it seems like there is an attempt to enter that world and see it from the inside without passing judgments on it. There is a defiant and liberal use of Urdu and Hindi words in the narrative that are neither italicised nor explained away in appendices or a glossary.

Only seems because, the glossing takes place more subtly, with the words explained away unobtrusively in parenthesis. And considering that she gets her history from the likes of Mason, she only ends up reinforcing the Orientalist images of opulence, grandeur, intrigue, decadence and irrationality, in an Escherian sliding of backgrounds and foregrounds. In the midst of bazaar scenes with (what else?) cows placidly lounging in the midst of hectic activity, monkey shows, jugglers throwing flames around, elephant fights, tiger hunts and snake charmers and sons forever plotting the deaths of brothers and fathers is the story of one woman’s love for Jehangir that might as well provide the script for Bollywood’s next NRI blockbuster. Like Mira Nair’s Kamasutra which, under the guise of exploring class and gender issues actually only gives a spectacle of India as the West would like to see it (or is it the other way round?). It is a painless transition from Mason’s fantasy as history to history as commodity.

This packaging of the “Indian” as exotic is rather ironic because, in a globalised environment that can cut both ways, it is we “Indians”, resident and non-resident, who are doing the packaging; picking, appropriating and marketing the exotic for consumption abroad. A kind of Rushdie in reverse gear. One of the prerogatives resulting from the upper-class post-colonial’s access to and familiarity with two cultures. One almost sighs in longing for good-old Mason. He at least had the excuse of being a foreigner. Orientalism’s modern homegrown mutations are trickier because they are familiar with and use the tools of the post-colonial and the post-modern.

The Twentieth Wife, Indu Sundaresan, Penguin India, 2002, p.388, Rs. 295.